Added 25.12.12. New info. added 14.7.16.

IN PROGRESS — NOT FOR PUBLICATION

The Statue of Lieutenant Fitzgibbon in Limerick

Erected 1857? Destroyed 1930

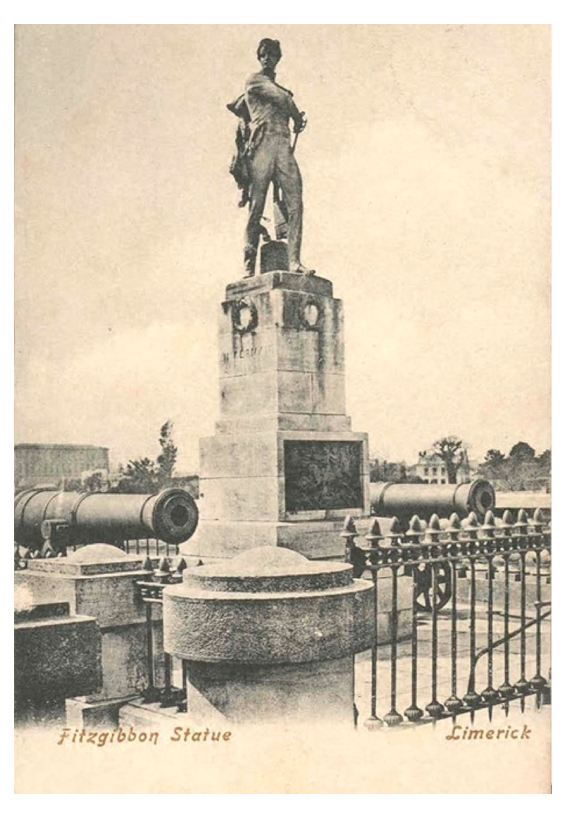

John Fitzgibbon, 8th Hussars, Statue — postcard image

(Click on image to enlarge)

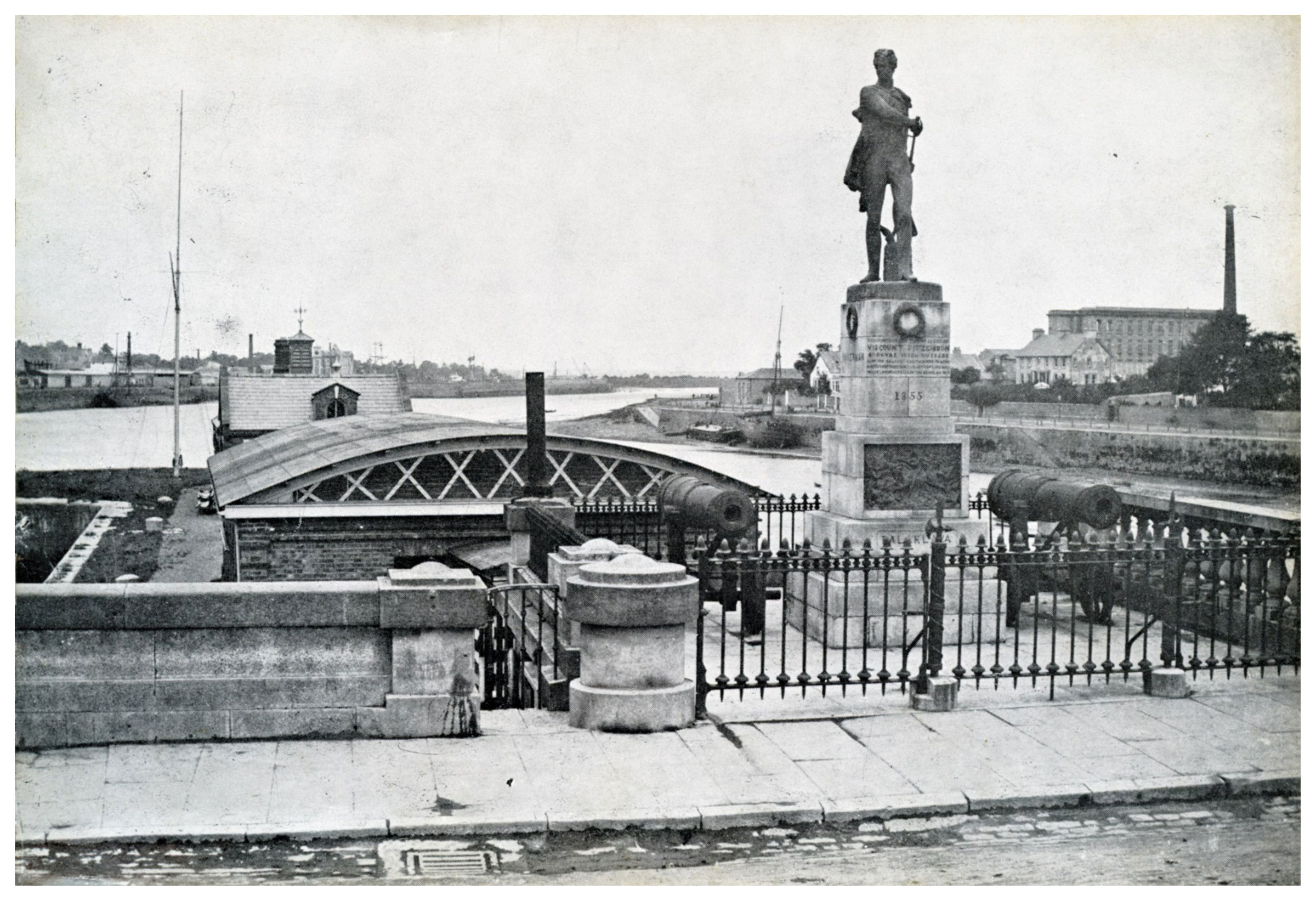

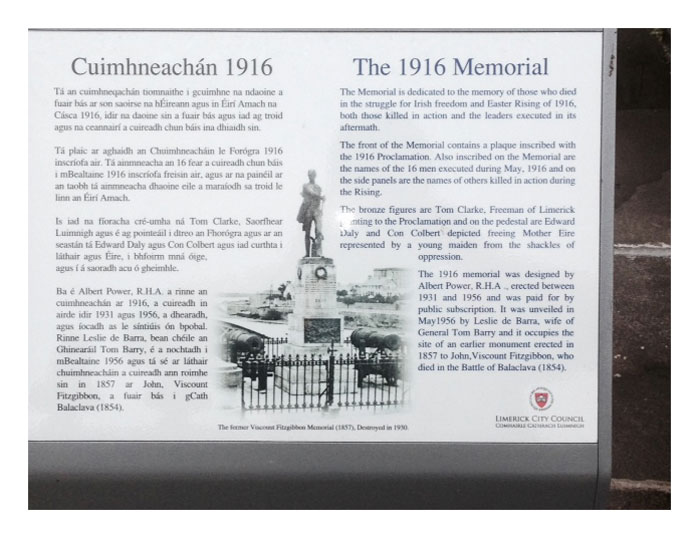

A statue of John Fitzgibbon in the uniform of the 8th Hussars once stood on Wellesley [now called Sarsfield] Bridge in Limerick, but after several failed attempts by Republicans to destroy it (e.g. at least two attempts in 1877), it was successfully blown up in 1930 [?]. The massive plinth on which it stood survived, however, and Fitzgibbon's statue was later replaced by one of

[The "Wellesley" refers not to the Iron Duke but to his brother, Richard Colley Wesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley (1760 — 1842). He was Governor-General of India 1798 — 1805 and Lord Lieutenant of Ireland [dates?]. It was re-named Sarsfield Bridge, after, in [1880s]?]

-

[PB: Quote the text on the plinth about Limerick men in the Crimea. And NB 1091 John Fitzgibbon, 8th Hussars, his namesake in the same regiment, who also died.

Soon after Fitzgibbon's death on 25th October 1854, meetings were held and funds collected to erect a substantial statue to him (with some reference also to other Limerick men killed in the Crimea) (the best source on these meetings is T. Moloney, "The Fitzgibbon Memorial at Limerick", The Irish Sword, vol.xxvi, pp.401-410 ).

Testimonial meeting in Limerick to raise funds to erect a statue, as reported in The Freeman's Journal, 11th of April 1855

(Click on image to enlarge)

The Right Worshipful Henry O'Shea, Mayor of Limerick:

"the brilliant charge of Balaklava, wherein the gallant Lord Fitzgibbon fell, was never surpassed in ancient or modern warfare, and in the pages of history it will for ever live (cheers). Well, indeed, might this be called a brilliant, but dreadful, charge; and amongst the gallant soldiers who there fell was the chivalrous Lord Fitzgibbon, the only son of the Earl of Clare (hear).

There he lay in front, all covered with wounds; and thus he died a glorious death — a soldier's death — the death of the brave (great sensation); and, as his life-blood was gushing from his noble heart, I can well imagine him thinking of his beloved home and country, and asking within himself if in his own land any memorial would be raised to commemorate the daring deeds of those who well upon that glorious day?

And here we are now assembled to answer such an appeal, by taking the necessary steps for erecting within our city some testimonial worthy of the memory of Lord Fitzgibbon and his brave companions in arms, natives of the county and city of Limerick, who shared in the glories of the Crimean war (cheers)."

Counter-claims were made that Irish nationalist heroes had more right to be commemorated, and there was considerable debate about whether it should be Fitzgibbon or Daniel O'Connell who should be displayed in the most prominent site in the City. (O'Connell ultimately won).

Some critics argued that young Fitzgibbon had done very little to earn the honour...

TIDY UP, EXTRACT, SUMMARISE...

Councillor Eugene O'Callaghan...protested against the donation of the site at the Crescent [a prime location in the fashionable area of Newtown Pery], ostensibly because the Viscount was of such an age that he was quite unknown to his (O'Callaghan's) constituents and because the people of Limerick did not desire such a memorial. O'Callaghan asserted that the unfortunate Viscount had:

"nothing to do with the planning or conduct of that cavalry charge; he merely rushed on with the rest, obeying the orders of his superiors... We are not told that Lord Fitzgibbon did this or did anything... Indeed it was for a considerable time [a] matter of painful doubt whether he fell at all. I say that under these circumstances, it is preposterous to call upon an enlightened city like this to commemorate the achievements of Lord Fitzgibbon by a public monument."

[Councillor John Barry] expressed a view not dissimilar to that of O'Callaghan, saying that he could not understand how such a young man as the Viscount 'was entitled to this honour': 'Was he a great warrior? He did not place the standard on the walls of Alma'. [Councillor] McMahon believed that 'The Cathedral [St Mary's] or some such place would be more fitting, and he thought the memory of Lord Fitzgibbon would be thus as much respected as if the monument was erected in the centre of the Crescent'.

Echoing this view, the Catholic Nationalist Limerick Reporter suggested that there was plenty of space for the memorial in the Cathedral [St Mary's], 'in a mortuary chapel...' where 'not only would no word be uttered in its dispraise, but there are many who would mingle their sympathies with those of the admirers of the deceased', and where there would not be interference of any kind.'

Notwithstanding the terms of the publicly expressed views, there was a subliminal message: the real objection was to the siting of the intended structure in a place as prominent as the Crescent, where its presence might have been seen, at a time when a moderate Catholic constitutional nationalism was gaining ground, as signifying the City's loyalty to the crown. The objectors saw it as necessary to sideline the intended monument to a location where few people would see it.

[Source: Tadhg Moloney, "The Fitzgibbon Memorial at Limerick", The Irish Sword, vol.xxvi, pp.401-410 [2007?] [Journal of The Military History Society of Ireland].

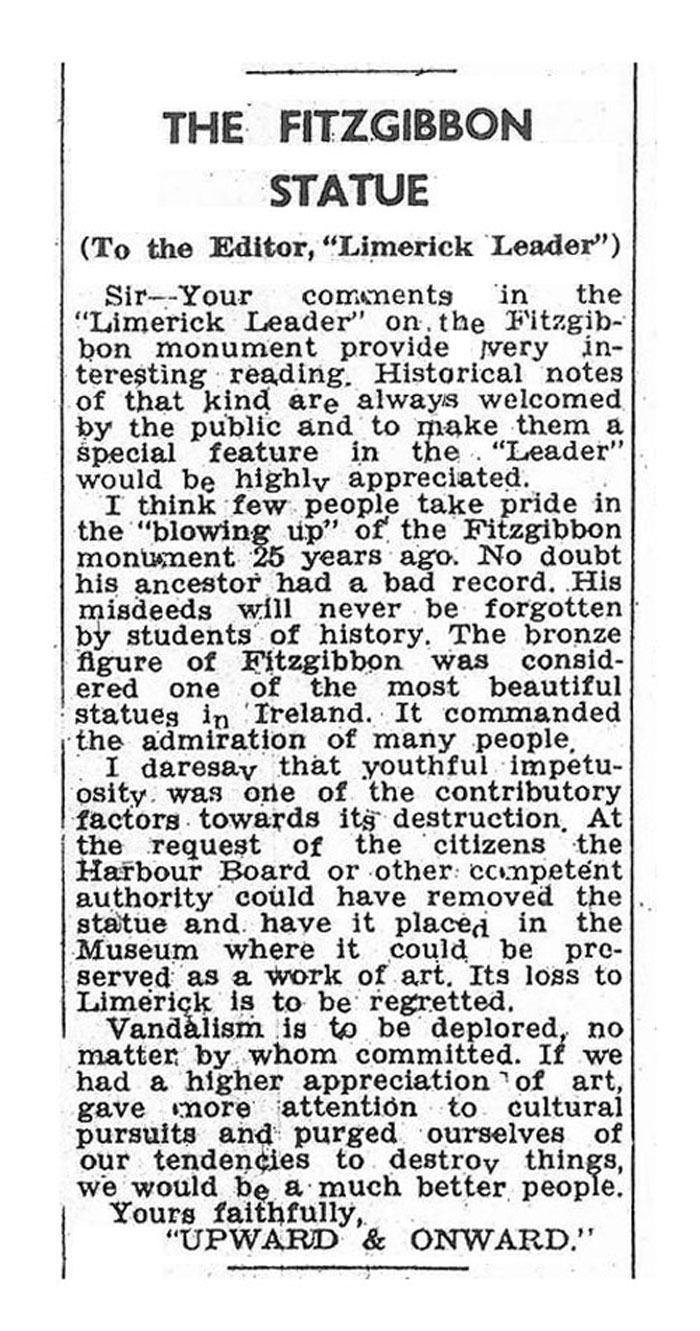

[PB: It would be good to try to understand and express why the statue became the target of such hostility (to many, if not to all). I vaguely recall reading that the sword was damaged quite early (twisted?), and left that way for many years. ADD SECTIONS FROM MOLONEY that the target was always JF's grandfather, who had promoted the disastrous Act of Union [1800-1], since young Fitzgibbon was, as it were, blameless, and his father had been active in promoting Catholic and national interests.]

A correspondent signing himself 'A Citizen" did his utmost to put the local conservatives in a bad light, by claiming that the Tories on the Town Council had 'stolen a march on public opinion'. He accused them of taking possession of a site at the Crescent and of taking measurements with an immediacy for the erection of the monument. This charge was of course without foundation.

Furthermore he expressed in very nationalistic terms the view that this monument would be 'a slur on the fame of our city! A monument to the grandson of the traitor who sold his country'.

This last view was based on a very selective reading of history. There was no reference to the Viscount's father, who had supported Daniel O'Connell during his quest for Catholic Emancipation; who, during the Famine, had 'generously assisted emigrants', which left him in dire financial straits; and who, as lord-lieutenant for County Limerick, 'drew criticism for filling the post of deputy-lieutenant exclusively with Catholics.' 23 It seems that the sins of the grandfather were to be visited on the grandson, as they were to be again seventy-three and a half years later.

[PB: The quotations in the last paragraph are taken from Ann C. Kavanaugh, John Fitzgibbon, Earl of Clare: A Study of Personality and Politics (Dublin, 1997), pp.395-6.]

Elsewhere, Moloney writes:

[The mayor] set the historical record straight when he reminded his fellow Roman Catholics that Catholic Emancipation could not have been achieved without the support 'of the liberal Protestants of Ireland', which included the Viscount's father, who were ever to be found fighting by our side, and without their generous aid, the glorious victory would have been long delayed, if it would have ever been achieved (Moloney, p.404).

[Is the following EJB's version or Constantine Fitzgibbon's?]

There used to be a scurrilous poem about the statue in Limerick which ran:

"There he stands in the open air

The bastard son of the late Lord Clare

They call him Fitzgibbon, but his name is Moore,

'Cause his father was a cuckold

And his mother was a whore."

This is surely unfair — it was his elder brother who was born out of wedlock before the third Earl of Clare married the lady in question, so John, born after their marriage, became heir to the title.

[PB:I vaguely recall the author has been identified as a famous scurrilous journalist of the day?]

[PB: See pdf in notes of Constance Fitzgibbon, A Visit to Limerick, 1952.]

[PB: Extracts from Reputations: Nineteenth-Century Monuments in Limerick, Judith Hill, [source and date?] — an excellent essay.]

"Reputations: Nineteenth-Century Monuments in Limerick"

Extract from Reputations: Nineteenth-Century Monuments in Limerick, Judith Hill, [source and date?]

Monuments were to the nineteenth-century city what corporate identity is to the modern business; they projected an image that spoke of specific character, unity and confidence. Is this just the impression gained in retrospect by the image-conscious late twentieth century or is this what they were intended to do?

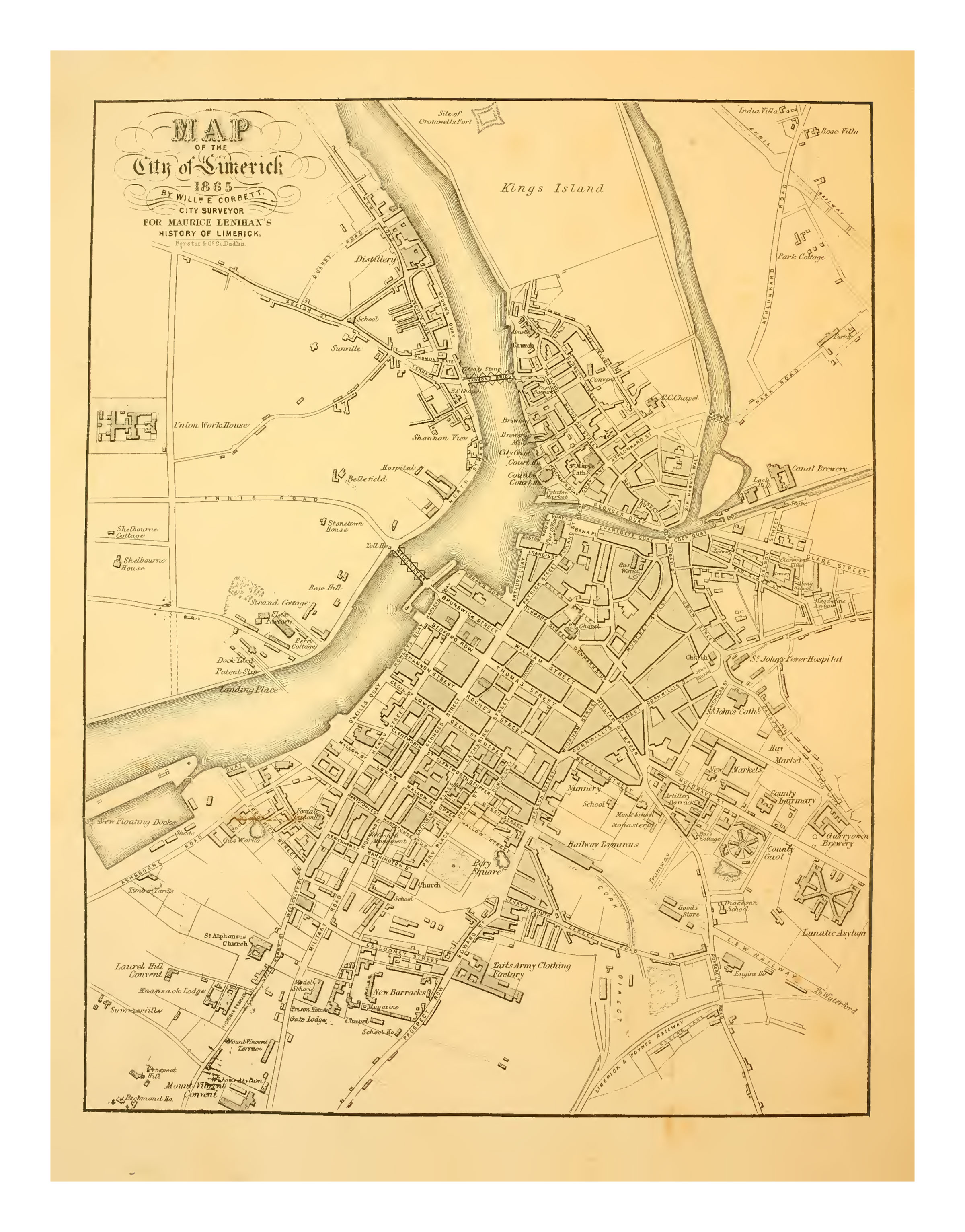

One of the fascinating characteristics of monuments is the way that, once erected, they take on a life of their own. So, although today Limerick's nineteenth-century monuments are frequently used in civic publicity, business logos and on postcards, not all the monuments are represented equally: the Treaty Stone is pre-eminent; Patrick Sarsfield is quite popular; Daniel O'Connell and Thomas Spring Rice are mainly confined to postcards; and Fitzgibbon, who was thrown into the Shannon in the early hours of a June morning in 1931 [?] and later replaced by a memorial to 1916, can only be seen in archival photographs.

Just as this ordering reflects contemporary values distilled from tradition, aesthetic awareness and political allegiance, so the first appearance of the monuments reflected current values. A study of the nineteenth century monuments — many of which were erected through public subscription and all of which were allocated sites through negotiation with the Limerick Corporation or official bodies — can tell us much about political attitudes and power structures.

Such a study of the monuments collected in one place provides an opportunity to reflect on the extent to which they were intended to be ambassadors for that place, and how they have acted subsequently...

On 17 May 1855, two monuments were discussed at a Corporation meeting. (5) An announcement had been made that £1,040 had been collected for a statue to be erected in Limerick to Lord Viscount Fitzgibbon, who had died at the battle of Balaclava in the Crimean War, and the mayor, who was chairing the proceedings, had suggested that it be given a site at the centre of The Crescent.

Several of those present had, since 1852, been involved in organising the funding of a monument to Daniel O'Connell [PB: add link to]. They had earmarked this prominent location — the highest and widest point in George's Street — for the monument, and they argued that the Town Council would have to be consulted.

The O'Connell monument committee was galvanised into action; meetings were held; a sculptor contacted; a further appeal was launched for subscriptions. The Limerick Reporter and Tipperary Vindicator argued forcefully for the O'Connell monument and at a subsequent meeting the Council voted to adopt The Crescent site for the O'Connell monument.

The controversy reflected two different political camps within the Corporation — the older interest, Protestant, landed, Unionist — and the group left in the wake of O'Connell's political advance, Catholic and nationalist. In Limerick Corporation this latter group was represented by men such as Maurice Lenihan, who supported initiatives to establish a Catholic university in Ireland and dis-establish the Church of Ireland, and who had voted for Repeal. Lenihan promoted nationalist ideas in his newspaper, The Limerick Reporter and Tipperary Vindicator, and he was a city councillor. He had proposed the O'Connell monument.

Neither O'Connell nor Fitzgibbon had more than a tenuous connection with Limerick. O'Connell had held 'monster meetings' in the vicinity of the city and visited it several times, but it was as MP of Clare, elected in the old courthouse in Ennis, that he first sat in parliament. (6) Fitzgibbon was the son of the third Earl of Clare, whose family lived at Mount Shannon, near Limerick.

The statues of these figures were not erected primarily to represent the city. Instead the act of their erection was intended to demonstrate the city's credentials. Lenihan wrote in his History of Limerick: 'There being no appearance of the national monument in Dublin, the propriety of renewed local exertion was mooted to commemorate the fame of the illustrious chieftain in 'the city of the violated treaty.' (7)

Limerick was the second city to erect a monument to O'Connell. (In August, 1846, a ten feet high statue of O'Connell had been erected at Dublin's City Hall, but the national testimonial in Dublin was not proposed until 1862.) Fitzgibbon was a war hero. The Crimean War was more often recognised by the display of captured cannon; Limerick also demonstrated keenness in its desire to erect a statue.

The contest between two statues for one site suggests that monument-building was a common phenomenon in Ireland at this time. This was not the case. The Nation, a nationalist newspaper, had called for more statues of Irishmen in Dublin in 1843, but by 1855 only one statue was being prepared — a monument to the popular poet, Thomas Moore. A group in Limerick had advertised for sculptors to submit models for a monument to Patrick Sarsfield in 1845, but Joseph Robinson Kirk's model had been turned down and the project dropped.(8)

Different political affiliations in Limerick in 1855 did not translate into different styles. Instead, both monuments were examples of the mid-Victorian way of celebrating Great Men that was popular in Britain. Portrait statues were erected on moderately-sized plinths so that the viewer could appreciate the details of the sculptured figure — the clothes, the expression, the pose — each designed to elicit admiration and provide an example.

There were differences, however, deriving from the artists commissioned. John Hogan (1800-58), a sculptor who had spent much of his life in Rome, and who had carved the marble statue of O'Connell for the City Hall in Dublin in 1846, was an exponent of the neo-classical style. He made a bronze figure of O'Connell for Limerick in which O'Connell, sheathed in a Roman toga and holding a text of the Act of Catholic Emancipation, was presented as the dignified elder statesman. Hogan did for O'Connell in Limerick what he had done for him in Dublin: he made an Irish leader into a classical hero and thus elevated his subject in the vocabulary of neo-classicism. '... It is my opinion', he said, "that the classic draperies, which have been so long used, raise the artistic character of the work and the dignity of the subject'.(9)

Patrick MacDowell (1799 — 1870), on the other hand, presented Fitzgibbon as a dashing young army officer in the act of unsheathing his sword; another idealisation but not as dependent on classical style and accoutrements as Hogan's.

The statue of Fitzgibbon was erected on Wellesley Bridge, which joined the city to County Clare; its presence there marked the landed interest that had promoted the building of the bridge in the 1820s.

Meanwhile, the presence of the figure of O'Connell can be read as part of the redefining of the character of Newtown Pery through the building of national schools, Catholic churches and other institutions associated with a democratising of politics in the nineteenth century. The older interest remained but it could feel threatened; the wife of John Russell, Quaker industrialist, merchant and speculator, refused to open the blinds of the windows in her Crescent house for fear of encountering the masterful gaze of O'Connell.

When the O'Connell monument was unveiled in 1857 it was O'Connell's role in securing the Act of Catholic Emancipation in 1829 that was emphasised. The MP for the city, Sergeant O'Brien, made a speech in which he painted Irish Catholic history in a few sweeping strokes which also put Limerick at the centre:

Here was the Capitulation and the Treaty, so honourable to the Irish Catholics, so disgraceful to our rulers by whom the provisions of that Treaty were shamefully and unhesitatingly violated. By their perfidious conduct we then lost that religious freedom which after nearly 150 years was again recovered under the guidance of O'Connell. It is right therefore that Limerick should be foremost in paying this homage to his memory. (11)

The signing of the Treaty in Limerick in 1691 had concluded the wars of the seventeenth century and heralded what might be described as the Protestant peace, the period when British authority was secured through the re-organisation of government and the successful establishment of Protestant landowning families. The Treaty had promised rights to Catholics but, with the subsequent passing of the Penal Laws, Catholics lost much of their political power and many of their civil rights.

[...]

_______________

NOTES

1. See map of Limerick, 1827, in Judith Hill, The Building of Limerick, 1991, p.

2. See M.O. hEochaidh, Modhschoil Luimnigh 1855-1986, 1986, p.50-1.

3. Drawing RIBA, London.

4. Now the art gallery, erected in 1906.

5. Maurice Lenihan, Limerick: Its Histories and Antiquities, 1867, p.

6. In 1865 a column topped by a statue of O'Connell was erected on the site of the old courthouse in Ennis.

7. Lenihan, op. cit., p. 511.

8. Lenihan, op. cit., p. 505.

9. The Limerick Chronicle, 19 August.

10. A Belfast-born sculptor who was working in London, MacDowell made monuments to the Marchioness of Donegal and statues of the Earl of Belfast for his native city, and of the Earl of Eglinton and Winton for Dublin.

11. The Limerick Chronicle, 19 August,

12. Breandan Mac Giolla Choille, "Mourning the Martyrs", North Munster Antiquarian Journal, IX-X 1967, pp. 173-205.

13. From Davis, 'National Art' in Essays, quoted in Jeanne Sheehy, The Rediscovery of Ireland's Past the Celtic Revival 1830-1930, p. 30.

14. Limerick Chronicle, 26 July, 1881.

15. Limerick Chronicle, July and August, 1881, for the debate about Henry O'Shea's role in the design of the statue, and the controversy about the siting of the monument.

16. Limerick Chronicle, 19 July, 1881.

Judith Hill's book, A History of Public Sculpture in Ireland, will be published by Four Courts Press in Autumn, 1997.