LIVES OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE

The E.J. Boys Archive

Added 9,1,2017.

1029, Private Gordon David RAMSEY - 17th Lancers

(Click on image to enlarge)

THE REIGN OF TERROR:

A NARRATIVE OF FACTS CONCERNING EX-GOVERNOR EYRE, GEORGE WILLIAM GORDON, THE JAMAICA ATROCITIES.

HENRY BLEBY

AUTHOR OF THE "DEATH STRUGGLES OF SLAVERY," "SCENES IN THE CABIBBEAN SEA," "PREDESTINATION NOT FATALISM," "TRUE AND FALSE APOSTLES," "THE WICKEDNESS AND DOOM OF THE PAPACY," ETC., ETC.

"The hell-like saturnalia of martial law." — Mr. Roundell, Secretary to the Royal Commission to Jamaica.

LONDON

1868.

PRINTED BY WILLIAM NICHOLS, 46, HOXTON SQUARE.

[PB: There are numerous references to Gordon Ramsay in what follows - these have been highlighted. The main section dealing with him is here (pp.71-91). I have not fully copy-edited the transcription, which was based on a very imperfect OCR'd version. Do not quote without checking against a pdf of the original. There are a number of versions available online, and here. NB There is a brief and dismissive reference to GDR's military career on p.77.]

PREFACE

The following pages are designed to exhibit the truth in defence of a deeply wronged and slandered people. Wide-spread misapprehension and ignorance prevail concerning the disturbances in Jamaica in 1865, and the measures adopted by the local authorities with respect to them. Few persons have a correct idea of the facts associated with the outbreak, or of the atrocities which were practised during martial law. The writer feels it to be due to the murdered members of the Church he belongs to, whose blood still cries from the ground; to the black and coloured inhabitants of the British West India Colonies, who are a meek, long-suffering, and forgiving race, and not the monsters of cruelty and vengeance they have been represented; to the Missionary Churches of the West Indies; and, above all, to the cause of truth and righteousness, to give to the religious public such a brief, consecutive narrative as may help those who are candid and right-minded to arrive at right conclusions concerning the tragedy, and the several parties who were prominently concerned therein. Such a narrative will be found in this publication; which, it is hoped, will tend to neutralize, in some measure, the great wrong that was done, when some Christian Ministers in Jamaica, panic-stricken, and ignorant of many of the horrible deeds which had been enacted, forgot what was due to the people of their charge, and appended their signatures to complimentary addresses to men whose proceedings have been shown, by the results of official investigation, to be deserving of the utmost reprobation. Those who desire more fully to know the details of this tale of horror, will do well to read the "Parliamentary Blue Books" relating to the Jamaica disturbances, and the inquiry of the Royal Commissioners concerning them; "Jamaica and the Colonial Question," by the Hon. G. Price; and the series of Papers by the Jamaica Committee.

The title which this pamphlet bears has been adopted, because it is descriptive of the state of feeling that prevailed in Jamaica in the latter part of 1865, in consequence of the sanguinary tyranny of the authorities, and which even yet is far from having passed away. Many persons feared to write to their friends, because letters were broken open and in some cases stopped altogether by the Government; and multitudes, especially amongst the more intelligent and respectable coloured people, were afraid to speak upon passing events to each other, or whisper their thoughts in the privacy of their own domestic circle; lest, being overheard, they should be dragged to prison or to the gallows, or subjected, without trial, to the torture of "the wire-tailed cat." It is not too much to say that, for many months, the whole population of the land were paralysed with "terror."

CONTENTS.

Chap. I. — The national character dishonoured — Governor pyre — Panics in Jamaica easily created — Morant Bay outbreak- Causes of dissatisfaction amongst the people — Mis-government and corrupt legislation — Letter of Rev. Mr. Clarke Testimony of the Baptist Missionaries- Partiality and injustice of local courts — The Church establishment

Chap. II. — Dr. Underhill's letter — Condition of public feeling in St. Thomas-in-theist — George William Gordon — Birth and character>-Testimony of Dr. King — Dr. Kidders — Other testimony — Cases of oppression at Morant Bay — Mr. Gordon opposes misappropriation of public funds- Defeats measures of Governor Eyre — Gordon's letter to Colonial Secretary — Public Meetings relating to Dr. Underhill's letter. P.19.

Chap. III. — The Magistrates' Court at Morant Bay — Want of discretion — The Vestry Meeting — Assembling of the crowd — Petition of Paul Bogle and others — Petition suppressed by the Governor — Bearer of the Petition flogged — The attack of the Volunteers — Retaliation — The Court-house burnt, and the Custos and others killed — False reports concerning the mutilation of the slain — The outbreak a local riot, not a rebellion — Provoked by the authorities — Want of energy on the part of the Government P.35.

Chap. IV. — Savage reprisals — Martial law — The first victim and Governor Eyre — Barbarous atrocities of British officers and men — Colonel Hobbs and his victims — Tragic death of Hobbs — The gallant 6th Regiment Brutality of officers and men — Murder of Cherrington — Boy wantonly killed — Blind man slaughtered — James Johnson assassinated — Lame and helpless man shot — Attempt at villainy followed by murder — Cruel treatment of two men P. 4a

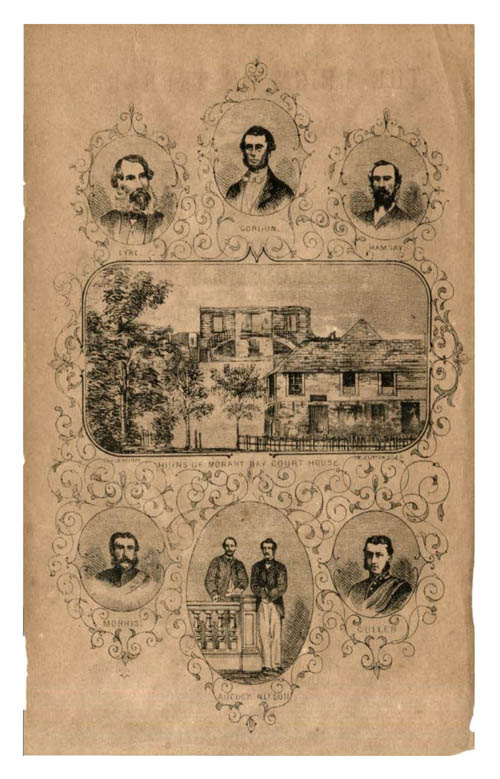

Chap. V. — Excesses of the troops — Rosa Maben shot — Joshua Francis killed — Two men murdered by Maroons — Bed-ridden man shot Murder of Sandy M'Pherson — Six innocent men slaughtered — Henry Dean — David Burke killed — Case of Andrew Quirke — Tragedy of James Williams — The Maroons of Jamaica — Dr. Morris and Ensign Cullen — Provost-Marshal Ramsay — His barbarities — Flogging with wire cats — Horrible treatment of Livingstone and his wife — Murders and atrocities by Ramsay — Flogging prisoners before execution — Murder of Marshall P.6.

Chap. VI. — Misrepresentation of Mr. Gordon — Arrested by Governor Eyre — Taken to Morant Bay — His brutal treatment -Nelson and Brand — The Court-Martial — Suppression of a letter by General Nelson, addressed to Gordon — Lord Chief Justice Cockburn pronounces the evidence " worthless " — The arrest and removal to Morant Bay illegal — Constitution of the Court illegal, and therefore without jurisdiction — Gordon's execution — Cruel and unjust treatment— His meek and. forgiving spirit — Last letter to his wife — Prosecution of Eyre, Nelson, and Brand Concluding remarks.' P..

CHAPTER I.

The philanthropy and the Christianity of Britain suffered a sad eclipse in the events which transpired in Jamaica during the latter part of 1865; and the honour of the British army and navy was shamefully sullied by the brutality of military and naval officers, and the readiness with which they lent themselves to perform deeds of cruelty, to which we can scarcely find a parallel amongst any savage people on the face of the earth. Englishmen felt the blush of shame and indignation mantling their cheeks, at the dishonour done to themselves and their country, when they saw one filling the proud position of their Queen's representative coming down from his high station, eagerly thrusting aside the policeman, and invading his office and duty, to capture and punish a political opponent, and also personally superintending and taking part in the cruel death of a poor Negro, who in the silence of the night is dragged from his home, and, after a wretched mockery of a trial which is a burlesque upon the administration of justice, is at once put to death with circumstances of revolting inhumanity. The shame and indignation thus felt was aggravated, as they read of men commanding vessels in Her Majesty's navy, performing the degrading duties of the hangman; and

[7]

others, bearing the commission of colonel or holdings other rank in the army, servilely obeying orders which it was an outrage against decency and humanity ta issue, and an insult to British officers to receive, and revelling with savage glee in the slaughter of defenceless and unresisting men. It is not to the honour of Britain that many, associated with the upper classes of society, have put themselves forward to shield the evil-doers in this case from the consequences of their misdeeds, and prevent that full and impartial inquiry which offended justice and humanity demanded when the character of the nation was so seriously compromised. It relieves in some measure, though it fails to vindicate, the sullied honour of the nation, that the force of public opinion compelled a reluctant Government to dismiss Governor Eyre from the position he had dishonoured, and appoint a Commission to bring to light the true facts of the case; also that the philanthropy and justice of the nation, represented by the Jamaica Committee, have, by forcing some of the guilty parties to the bar of justice, called forth that lucid and elaborate charge of Lord Chief Justice Cockburn, in the case of Nelson and Brand, which leaves a lasting stigma upon both branches of the public service, disgraced by the inhumanity of these officers, and brands ex- Governor Eyre with a degree of culpability which few men would like to bear with them to the grave and beyond it, as he will not fail to do.

The administration of Mr. Eyre is not likely to be soon forgotten in Jamaica. A few panic-stricken women, and some feeble-minded men — too feeble to be capable of forming an opinion themselves — may laud him as having saved them from a variety of perils which had no existence except in their own over-excited imagination; but all right-minded persons will

[8<]/p>

reprobate his government as by far the most disastrous and oppressive with which Jamaica has ever been afflicted. Unlettered and ignorant as most of the Negroes in Jamaica are they are fully awake to the fact that life and liberty were never more insecure within her shores than when they lay at the mercy of Mr. Eyre and his advisers. Many persons endeavour to palliate the faults of the ex-Governor, and find an excuse for the atrocities committed and sanctioned under his administration by urging that he was misled and acted under the influence of bad advisers. Were it even so, that would be no apology for such deeds as were perpetrated by him, and under his direction. He had no right, as the representative of England's Queen, to put his office in commission, so as to divest himself of the responsibilities inherently belonging to his position; nor could he in fact do so. The moral responsibility of all the murders of Negroes, and burning of Negro cottages and the innumerable outrages against person, life, and property that took place during the reign of terror called martial law, rests upon his head; and if mistaken men combine to screen him from legal punishment, his wrong-doing will not fail to be remembered when the Just and Holy One shall make inquisition for blood. Mr. Eyre was misled less by evil advisers than by his own prejudices and passions. His appointment was a mistake. He was an unfit man to be placed in such a high position, and to exercise such powers as those intrusted to him. His developments prove him to be a man of the most ordinary intellectual abilities, and also defective in some of those higher moral qualities without which no man is eminently great or good. Let the character of ex-Governor Eyre, as exhibited in his administration of the government of Jamaica, be analysed, and there will be found a deplorable

[4]

abnegation of the nobler elements which constitute the leading characteristics of a truly great and estimable public man, such as the late Lord Metcalfe, who for several years occupied the same position, and commanded in a high degree the confidence and esteem of all the inhabitants of Jamaica as their Mend and benefactor. Much has been said in the way of apology concerning the earlier developments of Mr. Eyre, and the amiable qualities he has exhibited on some occasions, his religious habits, &c. It may be all true; and just as much may be said with regard to many who have in the end stood out before the world shocking the sensibilities of men, when all that had hitherto appeared so fair and estimable in them was overcast and obliterated by the dark cloud of crime. For aught we know to the contrary, Mr. Eyre as an Australian explorer may have been as blameless as other travellers; and in his subsequent career as a colonial governor or sub-governor he may have kept himself from blameable excesses, because no powerful temptations presented themselves. But when the time of severe trial came to him in Jamaica, and he was placed in circumstances which demanded the exercise of high and noble qualities in the head of the government, to control and direct the current of passing events to a wise and favourable issue, then he signally failed; it became painfully evident that the commanding capabilities which the crisis required in the man at the helm of public affairs were mournfully lacking; and he stood revealed, the unenviable bearer of the responsibilities attached to him in the charge of Chief Justice Cockburn, and author of what Mr. Boundell, the secretary of the Jamaica Royal Commission, appropriately designates "the hell-like saturnalia of martial law".

By the evidence taken on oath by the Royal

[5]

Commissioners to whom the important task of investigation was intrusted, and who were armed with authority to compel the attendance and testimony of witnesses of all classes from ex-Governor Eyre downwards, it is clearly shown that the outbreak at Morant Bay, in the parish of St. Thomas-in-the-East, was simply a local riot, magnified by the craven fears of the civil and military authorities of the island into a dreadful rebellion" and made the occasion and pretext for shocking excesses, to which it will be difficult to find a parallel in British colonial history. During the dark days of slavery, panics not unfrequently occurred in Jamaica, proving the chronic state of fear and apprehension in which the colonists lived, while they reaped the profits of a system fraught with cruel injustice and oppression to the African race, so long trodden down and plundered by the professedly Christian nations of Europe. These were sometimes attended by circumstances exceedingly ludicrous, arising out of the trifling facts which were sufficient to throw a large portion of the community into a condition of the wildest excitement and dismay. In the July and August numbers of the ' Wesleyan Methodist Magazine ' for 1863, more than two years before the late tragedy in Jamaica occurred, there appeared an account, by the present writer, of a widespread panic in the parish where the late outbreak took place, nearly leading to the proclamation of martial law, — and all arising from the trifling incident of a Methodist Society-ticket being found in the box of a deceased slave by the plantation authorities, bearing the printed inscription, ' The kingdom of heaven suffered violence, and the violent take it by force. ' Too ignorant to understand that this was only a verse of the New Testament, which was printed on the ticket and given to the possessor of it as a token of Church

[6]

membership in the Methodist Society, the intelligent officials on the estate, and the astute magistrates, and other authorities of the parish, to whom the circumstance had been referred as wearing a most suspicious aspect, at once jumped to the conclusion that some fearful conspiracy was on foot to destroy the lives of the white inhabitants, of which this / seditious paper ' furnished the ' proof strong as holy writ/ When it further came to light that the Methodist Missionary residing in the town had given out some hundreds of similar documents among the slaves in the neighbourhood, nothing could be more certain, in the estimation of these wise men, than that this most timely, discovery of the dreadful plot had saved the island from all the terrible consequences of a slave rebellion. The militia were called out, and the parochial authorities assembled in all possible haste; scores, if not hundreds, of poor blacks, to their unutterable surprise, were captured. It was gravely proposed that the island should be proclaimed under martial law; and the wildest excitement and terror prevailed, until the Methodist preacher, who had been summoned before the civil and military authorities, assembled in solemn conclave, revealed the hitherto unsuspected truth, that ' the highly seditious words " on the supposed treasonable documents were simply a quotation from St. Matthew's Gospel; (proof of which was given, after some delay in hunting up the fragment of a Bible used for swearing witnesses in the parochial courts;) and that the paper which had created such a profound sensation had been given in recognition of the fact that the deceased slave was a communicant in the Methodist Church. Thus fortunately the bubble burst before any serious evil had been done.

An incident equally insignificant constituted the principal, if not the only basis upon which ex-Governor

[7]

Eyre rested the assertion that a terrible plot had been formed against the Government, and also involving in its objects the destruction of the white and coloured, as distinguished from the black, population; thereby throwing the whole country into a panic it has not yet recovered from, and such as could lead even tender-hearted women to palliate and excuse acts of cruelty and atrocity, against which under other circumstances their whole nature would have revolted. It is not one of the least of Mr. Eyre's misdoings that he palmed upon the community he was unfortunately appointed to govern, and as far as he could upon the British Government and upon the world, the most groundless slanders against the Negro population of Jamaica, and falsely charged upon them the intention to commit crimes which never had a place in their imagination, holding up to public reprobation as monsters of cruelty and crime a people as humane and well-disposed as any class of peasantry in Her Majesty's dominions.

When the Royal Commissioners had finished their arduous labours, after the most elaborate and searching investigation, they found no traces of the plot which I Mr. Eyre and his coadjutors had conjured up to \ frighten themselves and the peaceful inhabitants of the island. It has since transpired that the trifling incident, exalted and magnified by fear into positive proof that a barbarous massacre of the white and coloured inhabitants was in contemplation, admits of a most simple and natural explanation. With many other bug-a-boo stories, put forth to alarm a too credulous people, it was stated that amongst the papers of Mr. O. W. Gordon, when examined by the authorities, there had been discovered a plan of Kingston, the principal city of the island, on which were marked the several places of rendezvous where the rebel blacks were to

[8]

assemble for the purpose of capturing and burning the city and destroying the inhabitants. The terror produced by this statement was indescribable; and multitudes were afraid to go to bed at night, lest they should be massacred as they slept, or only awake to find burning and bloodshed all around them. This state of terror lasted for weeks, even after the so-called rebellion had been put down according to official announcement; it being far more easy to excite than to allay the fears of the people. And after all the stir made about the discovery of this famous paper, which was to prove G. W. Gordon a more wicked and sanguinary conspirator than Guy Fawkes himself, it turned out to be nothing more than the mischievous prank of an idle boy. Some years ago a youth, long since advanced to manhood, was employed in some inferior clerkship in G. W. Gordon's office or counting-house; and in an idle mood he one day amused himself with sketching from memory a rude plan of the city, (Kingston,) placing marks at certain places that possessed for unexplained reasons some sort of interest to himself. This was placed amongst other miscellaneous papers in his desk, and was forgotten. There it remained unnoticed for years, until the youth had passed into manhood and the time came when it pleased Governor Eyre to apprehend Mr. Gordon, and carry him to Morant Bay to be tried and put to death. His papers being then seized and examined, this boyish production came to light, and, without further investigation, was hastily pronounced by the sagacious helpers and advisers of Mr. Eyre to be indisputable proof of a conspiracy amongst the blacks, of which Mr. Gordon was the promoter and abettor, to massacre the white and coloured inhabitants, and burn the city. Thus it was that, scared by shadows from which no man of true courage and

[9]

self-possession would have apprehended any danger the local authorities terrified the people of Jamaica with the groundless fears which had taken possession of their own minds to the exclusion of all that was manly and dignified and sanctioned the atrocities that are so strongly denounced in the admirable charge of the Lord Chief Justice of England as offences against British law and humanity of no common degree.

The riot at Morant Bay was a sudden outburst of popular fury, unconnected with any plot, and confined to the parish and neighbourhood in which it originated; but resulting from a general feeling of discontent which had long been chronic among the black population. Its causes were both proximate and remote, reaching back to the time immediately succeeding the era of emancipation. Those who are acquainted with the history of events in Jamaica from 1834 will recognise in the Morant Bay riot one of the fruits of the misgovernment and mal-administration by which the labouring classes had been oppressed from the time they were released from the shackles of slavery. The planting interest, so called, has always been dominant, infusing its own evil selfish spirit into the legislation of the colony, and controlling the administration of the laws for its own purposes, more especially in the inferior courts. By a persistent attempt, extending over more than thirty years, to engraft a new system of slavery upon the freedom which the philanthropy of the British nation had wrought out for the colonies, they engendered a spirit of mutual hostility between the proprietary and labouring classes, and produced »a want of confidence which has been fatal to the interests of most of the Jamaica landholders, and brought their once splendid estates to ruin; while it has been disastrous to the civilization and well-being of the people them-

[10]

selves. In the legislature, the principal object of the ruling party, never lost sight of, was to keep down the emancipated classes, and so shape the laws enacted from time to time that the great burden of taxation should fall upon them, and as lightly as possible upon their employers. The peasantry were even compelled to pay a most unequal share of the enormous expense incurred in several abortive schemes of immigration, intended solely to lower and keep down, as near starvation-point as possible, the wages they were to receive for their labour. This suicidal policy was persisted in, until the black labourers, systematically oppressed and defrauded by the hirelings who were chiefly intrusted with the charge of the plantations, were driven in self-defence to purchase, and depend for sustenance upon, their own small freeholds; and thus a vast number of valuable estates, which, under wise and just management, would have continued to yield an ample income to their absentee proprietors, were thrown out of cultivation, and left to be overrun with bush. Under such circumstances, it is no wonder that a spirit of dissatisfaction spread widely amongst the people, and they lost confidence both in their employers and in the law-makers, highly appreciating the kind services of such men as Mr. G. W. Gordon, who boldly stood forth to expose and withstand the abuses by which the masses of the people were wronged. The Rev. Henry Clarke, island curate in the parish of Westmoreland, Jamaica, says:

"I have lived in this island during the last eighteen years, and have never had but one opinion of its government, which has been as corrupt, immoral, and oppressive, as any which has ever existed on the face of the earth. The whole influence of the Negro-hating, slavery-loving oligarchy which has ruled us has been openly and avowedly directed to the

[11]

impoverishing of the Negroes, in order that they might he able to compel them to work at their own rate of wages. This was the object of high import duties on the necessaries of life, and of Coolie immigration; which, of my own knowledge, I affirm to he a most atrocious form of the slave-trade and of slavery, expressly designed to lower the wages of the free Negro I attribute the existing poverty and demoralization among the people of my district, in a great measure, to the practice which the estates adopted of moving the Negro villages periodically, in order to prevent the labourers from profiting by the bread-fruits, cocoa-nuts, and other trees of slow growth, which they plant around their dwellings. Every village of the estates in this district, of five thousand inhabitants, has been moved within the last ten years; and as the people have to pull down and rebuild their cottages at their own expense, they have got into the way of erecting miserable little huts, in which the poor things are compelled to live, like pigs in a sty. I now humbly thank God that I have not appealed to Him in vain, and that He has scattered, as in a moment, that detestable oligarchy which for full two hundred years has bought, sold, flogged, robbed, maimed, tortured, and debauched the poor black people of Jamaica. The licentiousness of white men in Jamaica has been, and in many parts is still, as boundless as it is unblushing. The laws, as well as the records, of Jamaica are such as should make every honest Englishman blush with shame for the savage barbarities his countrymen are capable of, when left to the exercise of their natural propensities, unrestrained by any fear of public opinion or of the law. The Negroes are as loyal and peaceable, and would be as industrious and virtuous, as any people in the world, if they were wisely and honestly governed. I would not be understood to mean that Negroes are better than English labourers would be tinder like circumstances; but they certainly are not worse. All men are alike bad: it is only early training and the grace of God which make the difference in any of us. Now that Her Majesty has assumed the government of this island, I believe that peace and prosperity will prevail in it. But the

[12]

change must be complete to be effective; and there must be a complete sweep of Jamaica magistrates as well as of Jamaica legislators."

The Baptist Missionaries, in their statement presented to the Governor in 1865, make the following remarks:

"Numbers of persons in various parts of the island are in a starving condition The greater number have the greatest possible difficulty to support themselves and their families Among the foregoing causes of poverty and distress, we have referred your Excellency to the want of employment. In some districts, numbers of people are known to walk from six to thirty miles in search of work. Numbers, even in crop time, applying to the estates for employment, are turned back without obtaining it In all parts of the island a reduction of wages is expected, in most cases to the extent of from twenty-five to fifty per cent.

On very few properties can land be leased for a term of years; and, consequently, the small grower cannot risk the cultivation of produce which stands more than twelve months. Coffee, which takes three years to come into bearing, he cannot plant; because he would have no hope of reaping the benefit. In most cases the tenant is subject to a six months' notice to quit; and, not unfrequently, no sooner has he planted off an acre, say of ground provisions, than such a notice is served upon him Not only have ground provisions increased in price, but there has been a great advance in the price of imported food; while the price of clothing used by the people has been doubled, and in some places even trebled The increase which has taken place has been greatly augmented by the Legislature allowing the ad valorem duty of twelve and a half per cent. to remain the same The effect of placing heavy duties upon the food and clothing of the labouring classes has been to check improvement In many districts Creole labour

[13]

has been displaced wholly or in part by that of Coolies, Chinese, and Africans The cost of these immigration schemes to the country your Excellency will find to have been enormous. We believe an examination of the official returns will show that, from 1834 to the present time, it has not been much less than four hundred thousand pounds Complaints are made on account of the marked distinction, to the prejudice of the small settler, in favour of the great proprietor. The small settler has to pay for his horse or. mule eleven shillings, and for his ass three shillings and sixpence; while the working stock on the estates — steers, mules, and horned kind — are taxed only sixpence per head The peasantry suffer great hardships from the tardy administration of justice in some of our petty courts."

To the evils of partial and corrupt legislation were added those of partial and corrupt administration in the inferior local courts, amounting in many instances to a practical denial of justice. The planters themselves were largely intrusted with magisterial commissions, which enabled them to play into each other's hands in most cases involving questions between the employer and the employed, and cut off the weaker party from the redress which oft-inflicted wrong demanded. Questions of alleged damage by stray cattle, and of wages detained on various pretexts by the planters, afforded frequent opportunities of mutual obligation and accommodation, on the principle of ' Claw me, claw thee, ' between those who were most improperly intrusted with the administration of the laws. This evil prevailed to a fearful extent in St. Thomas-in-the-East, the scene of the late outbreak, where a faction, of which the rector and some members of his family were the head, ran riot in oppression and injustice of this kind. Nor was it confined to the locality that has been

[14]

mentioned. Mr. Justice Ker, one of the judges of Jamaica, says:

"I am called upon to observe, however, that St. Ann's has long bad a real grievance. That grievance is the fact, that the confidential clerk and manager of the leading mercantile firm there, the Messrs. Bravo, is at the same time clerk of the magistrates and deputy clerk of the peace. It is utterly impossible but that a very large proportion of the cases which come before the magistrates for adjudication are cases in which the Messrs. Bravo are either directly or indirectly interested, or in which they have, or are believed to have, a bias. But could an uninstructed population ever be persuaded that justice would be done in such cases P In point of fact, they do not believe it, as I have occasion very well to know. The influence exercised by the clerk of the magistrates over the Bench is necessarily very great, sometimes paramount. Some recent decisions from St. Ann's, which have been brought to my notice, have given me a most unfavourable impression of the administration of justice in that parish."

The following petition, presented to Governor Eyre a short time before the outbreak, and signed chiefly by those who afterwards perished in the bloody retribution exacted by Mr. Eyre and his advisers, will show how largely the abuses prevailing in the local courts of justice contributed to promote the prevalent feeling of discontent that led to the sad outburst of popular fury at Morant Bay:

"We most humbly beg to implore Your Majesty's attention to our humble communications. "When we were slaves, we never had such heavy work; and after having finished those number of chains, with the expectation, at the end of the week, to obtain the amount of six shillings, we generally get one shilling and sixpence to two shillings and sixpence for

[15]

the whole week's pay. The island has been rained consequently of the advantage that is taken of us by the managers of estates. Whenever we have a case which may be taken before the planter magistrates, they give us no satisfaction whatever, but combines with each other and takes away our rights. We most humbly beseech Your Majesty, that it may please Your Majesty to appoint a stipendiary magistrate to sit at every court day, as may enable us to obtain satisfaction. All we ask is, that Your Majesty may be pleased to consider over the state of this island, and render the poor some assistance; and that Your Majesty's life may be long spared, and that the blessings of those ready to perish may rest upon you.

"Andrew Eros," and thirty-nine others. " Sf, Thomas-irirtTie'Easty

"September 5th, 1865."

This petition, signed only five weeks before the outbreak, and placed in the bands of Mr. Eyre for transmission to Her Majesty, sheds light upon the causes of the riot, and serves to make manifest how painfully the people were feeling the oppressions heaped upon them by partial and class legislation and unjust interested magistrates, when those events occurred which immediately produced the catastrophe.

But one of the most crying evils under which Jamaica has groaned, is the incubus of a costly Established Church, which on the whole has done far more ta hinder than to promote the advancement of religion and civilization in the colony. Until the labours of Moravian and Wesleyan Missionaries awakened religious feelings amongst the black and coloured population, and through their agency. Churches were raised up and established amongst these despised and neglected masses; the clergy, supported in connexion with the

[16]

State in the several parishes, regarded the free coloured people and slaves as forming no part whatever of their spiritual and pastoral charge, and gave no more attention to them than they did to the cattle on the plantations. Then, influenced less by concern for the interests of immortal souls than by sectarian intolerance, they began, for the first time, to devote to these contemned classes some degree of attention, and to admit them, very sparingly and ungraciously, to Church privileges; and as the Missionaries, by their earnest and zealous labours, spread religious knowledge with its benign influences in various localities breaking up the fallow ground which none others thought of cultivating. Episcopal agents uniformly stepped in, and Episcopal churches were erected to absorb the fruit of missionary effort; all this being done at the public expense, and th6 Nonconformists themselves subjected to taxation, for the purpose of robbing them of the legitimate results of their self-denying toil. In this way Episcopalian churches (founded, in most cases, upon the results of missionary labour) were multiplied, until they overspread the land, furnishing lucrative situations for many of the sons and friends of the more influential Creole families, until the public burdens for State Church purposes were increased to the amount of some forty-five thousand pounds per annum, absorbing a large portion of the revenue of the island. The wrong done to the Wesley an and Baptist Churches especially, by this system of oppression, was very great. The membership of both these denominations was considerably in advance of that pertaining to the State Church; yet all were compelled alike to contribute to the taxation levied for the purpose of building Episcopalian places of worship, and paying the stipends of ministers, for the advantage of the more wealthy portion of the community; and then, unaided

[17]

by the revenues they were compelled to raise, they had to make similar provision for themselves. To aggravate the evil, the men, thus sustained by funds largely extorted from other religious communities, were very frequently possessed of none of the more important qualifications required for the office they filled; and, in too many instances, their lives were a reproach to the religion of which they professed to be the ministers. Nor is this evil yet removed. It is no violation of Christian charity, — for it is no violation of truth, — to say that a great proportion of the State clergy, whose support is largely derived, to the present day, from the taxation of Missionary and non-Episcopal churches in the West Indies, have no moral fitness for the office. But for this system of monstrous injustice, absorbing and neutralizing the effects of Missionary labour, the moral and religious condition of the British West Indian colonies would have been far in advance of what it now is. Whatever may be said concerning State-churchism in the mother country, nearly forty years observation and experience in various colonies has fully satisfied me that in the West Indies it has been the reverse of a blessing, and has produced a far greater amount of evil than of good. Recent events show that it has been a principal element of evil in Jamaica, and contributed in no small degree to augment the dissatisfaction prevailing amongst the labouring classes; especially when men, interested .in the welfare of the masses, like William Knibb and George William Gordon, called attention to the manner in which the entire population, of all denominations, were, upon the principle that " might is right/ compelled, whether they were willing or not, to give a portion of their hard earnings to provide religious advantages for the wealthier few. It

[18]

required clearer vision than large numbers of the people possessed to discover any shade of moral distinction between such a system of legalized plunder and highway robbery. In both cases it amounts to — " You must give us your property for our advantage; and if not, we will take it by force.''

CHAPTER II.

The operation of these and other similar causes produced that state of general dissatisfaction which became so strikingly manifest when the letter of Dr. Underhill, the Secretary of the Baptist Missionary Society, addressed to Mr. Cardwell, the Colonial Secretary, was made public; and large meetings, in all parts of the island, endorsed the complaints embodied in that letter concerning the grievances under which the industrial classes were groaning. But nowhere was this dissatisfaction more strongly cherished than amongst the large population of St. Thomas-in-the-East, where local oppression and abuse of authority extensively prevailed. Partiality and injustice reigned in the local courts, in which planter influence predominated, until the people had lost all hope of obtaining redress of any grievance; for every magistrate who endeavoured to exercise fair dealing, and hold the scales of justice evenly, was sure to be shuffled out of office on some pretence or other, or removed elsewhere, through the corrupt influences that had gained ascendancy in the parish. These were of such a nature as strikingly to illustrate the malign power of the Church establishment, and the gross oppression to which the people were subjected. The rector of the parish was one of the old-time, slave-holding clergymen, two of his sons filling public offices in the same parish; so that this family with its connexions gave whatever direction they pleased to parochial affairs: and the vestry, which this family largely controlled, possessing

[20]

the power to impose parochial taxes (including the demands made for various ecclesiastical purposes,) the Nonconformist congregations, which included a great majority of the people, were subjected to unjust burdens that were very keenly felt. The Custos — for so the principal magistrate in' the parish is designated, holding a position somewhat analogous to the Lord-Lieutenancy of an English county — was the unfortunate Baron Von Ketelholdt, who was among the earliest victims of the outbreak; and he was a man possessing but little strength of character, so that he was easily moulded to the purposes of the ruling faction, — a weakness which ultimately cost him his life. Large amounts had been levied, during several years past, by local taxation upon the people, to build a church in one of the parochial districts, where a new church was not truly required; for the character of the resident clergyman was so much at a discount that few cared to attend his ministry; and this church-building scheme was well known in the neighbourhood to be only a gross piece of jobbery, designed not so much to serve the public good as to put a large sum of money into the pocket of the clergyman himself, — the Rev. Mr. Herschell, — who was also among the early victims of the riot, and who, contrary to all precedent and all propriety, was suffered to become the contractor for the erection of this ecclesiastical structure. And his conduct in connexion therewith was such as to create much offence, and bring obloquy upon his name, which even the tragical circumstances of his death have not been sufficient to obliterate. Another extensive ecclesiastical structure, still standing in an unfinished state near to t lie scene of the outbreak at Morant Bay, was also commenced, at a heavy expense to the people of the parish; though the vast majority of them had no

[21]

manner of interest in these buildings which, if erected at all, should have been at the cost of those — the more wealthy class — for whose immediate benefit or convenience they were intended.

Under these complicated oppressions/ aggravated by drought 9,nd poverty, the labouring people groaned in St. Thomas-in-the-East; and when George William Gordon, whose tragic fate has called forth such widespread sympathy and indignation, interposed to obtain redress of existing grievances, he, at the instigation of the corrupt clique ruling over the parish, was treated by Governor Eyre with gross injustice, the sanctioning of which reflects but little honour upon the Duke of Newcastle, the Colonial Secretary of that day, and stands in unfavourable contrast with the proceedings of the Colonial Office when men like Sir George Murray, or Lord Goderich, were in power there. Mr. Gordon, like other men, doubtless had his infirmities; and perhaps it may be true that, if he had been somewhat less impulsive and imp6tuous, he might have accomplished a larger amount of good; but there is no reason to believe that he was otherwise than a good and sincere man advocating, from disinterested motives, the rights of a down-trodden people, and labouring with earnest zeal to obtain redress of the numerous wrongs to which he saw them subjected. As one of the landed proprietors of St. Thomas-in-the-East, and representing the parish in the colonial parliament with no mean ability, his influence was powerfully felt in the parish vestry, in opposition to the selfish faction dominant there; while he also stood forth as the stem uncompromising opponent of those measures which he deemed to be corrupt and oppressive in connexion with the administration of Governor Eyre.

To persons who are not acquainted with the real

[22]

merits of the case it may appear that, if Gordon was somewhat harshly treated, he deserved in great measure what was done to him, as a factious and interested demagogue, taking advantage of the ignorance of the masses to stir them up against lawful authority, and render them dissatisfied with their condition and their rulers. Nothing has been wanting on the part of Mr. Eyre and his adherents, to give this complexion to the case, and traduce the character of the murdered man: but a true insight into the facts warrants a widely different view, and shows that Gordon made himself enemies by his fidelity in exposing and rebuking real abuses both in parochial affairs and in the general government of the Colony, and at length became the innocent victim of political rancour, persecuted to death by as gross an abuse of trust, and as violent an outrage against law and justice, as the records of British Colonial history will furnish.

George William Gordon was born in slavery. He was the son of Mr. Joseph Gordon, who was a planting attorney on a large scale, having the oversight of a considerable number of plantations by power of attorney from the absentee proprietors, from which he derived an ample income. He was Custos of St. Andrew, the parish in which he resided; and he also represented the parish in the House of Assembly. The mother of G. W. Gordon was a slave; and, according to rule in such cases, the child followed the condition of the mother. But, by the profitable exercise of the intelligence and energy with which he was gifted, he acquired sufficient means to purchase his freedom and that of his slave-born sisters; and when, as the result of the changes brought about by the abolition of slavery, the once wealthy father became involved in pecuniary embarrassments, the son, born to an inheritance of shame and servitude.

[23]

nobly stepped forward to his help, and purchased the property of the father to leave him in possession of it and in the enjoyment of the earthly comforts to which he had been accustomed. At the same time he won his way to a position of respectability and influence, as a member of the Legislature and a proprietor of the soil. These unchallenged facts show that George William Gordon was, both intellectually and morally, a man of superior character. And the testimony of competent and highly respectable witnesses fully sustains this estimate of that deeply injured man.

The Rev. Dr. King, of the Church of Scotland, who knew him well, says:

"Without pronouncing any judgment on recent occurrences, I am free to say that nothing but a total transformation of .disposition, or unsettlement of reason, could involve such a man as he was in seditious schemes or bloody adventures. He was a member of a United Presbyterian Church in Kingston, of which I filled temporarily the pulpit. He aided and cheered me in the fulfilment of my duties. I stayed with him occasionally, and we had excursions together. I had every facility for knowing what was thought of him by judges, magistrates, clergymen, and society in general; and at that time every one, from the highest to the lowest, spoke of him with esteem. Mr. William Wemyss Anderson was one of the first who called my attention specially to him, by characterising him as a man of princely generosity and of unbounded benevolence."

Dr. Fiddes, a physician who stands at the head of his profession in Jamaica, and who knew Mr. Gordon from his youth, says:

"I had been well acquainted with Gordon during the last twenty years; and, although I always regarded him as rather eccentric in his views and notions of the people's rights, and somewhat peculiar in his religious observances, I

[24]

had nevertheless great respect for the power of his intellect and the innate force of his character. He was, moreover, a man of generous disposition, and possessed much kindness of heart. That he wished well to his country and countrymen, I am thoroughly convinced; that he ever counselled the people to the commission of acts of violence and murder, I do not believe."

''Mr. Gordon was personally known to me," says a member of the late Jamaica House of Assembly; "and Jamaica had a worthy and faithful son in him. It was impossible for him to escape the dangers which beset him, when he constantly proclaimed the wrongs done to the oppressed classes. I can bear witness to his faithful advocacy of the people's rights. I wish the Colony had fifty such men."

*"Few," says another witness who knew him well, " are willing to confront the wrong doings of men who hold a position of public and important trust. This, Mr. Gordon dared to do; and for this, I believe, he has been called to suffer. To the maliciousness which seems to have prompted some of Mr. Gordon's foes, there appears to be no bounds. I speak from personal knowledge of Mr. Gordon, when I state that a more kind-hearted, humane, and generous man was not to be found in that Colony. Whenever an object of distress presented itself, none was more liberal in administering relief, none felt more deeply for the woes of suffering humanity, or was more prompt in mitigating that suffering. When we couple these things with the fact that Mr. Gordon was one of the largest land proprietors in Jamaica, nothing, I think, shows more clearly the improbability of his being the instigator of the late outbreak."

Such was the man whom Governor Eyre seized upon, bearing him away from the bosom of his family to the scene of merciless slaughter, as an eagle bears its prey in its clutch; and, without one emotion of relenting or pity, handed him over to those amiable rivals of Cal-

[25]

craft, Messrs. Nelson and Brand, to be immolated upon the altar of political strife. A few facts may suffice to explain the rancour of the faction ruling the affairs of the parish against Mr. Gordon, and the envenomed feelings so manifest in the proceedings of Mr. Eyre towards this injured man.

The rector of St. Thomas-in-the-East, already referred to, being solicited for alms by a diseased wanderer, took the extraordinary course of sending the poor man to the lock-up: an act which he had no authority to perform, as he was not a magistrate. The wretched outcast, thus sent to a place used only for punishment, and having no better shelter assigned to him than the privy of the establishment in a most disgusting state of ' filthiness, died there, with no hand to aid him in his last moments, and was then buried, contrary to law, without an inquest being held. This outrage against humanity and justice Mr. G. W. Gordon — who was a member of the vestry, a magistrate, and the representative of the parish in the Legislative Assembly — brought under the notice of the Governor, calling in question the conduct of the rector, and requesting an investigation. Contrary to all propriety, the matter was referred for inquiry to the parochial authorities, who were themselves also implicated in suffering such a state of things to exist in the parish as this case disclosed, instead of being placed, as it should have been, in the hands of a commission composed of disinterested men. The result was what might have been expected, and doubtless what Governor Eyre desired. All fair inquiry was smothered, and the inhuman and illegal conduct of the rector, in sending a man to prison on account of his poverty, was represented as a sort of imitation of the Good Samaritan. It was made, in the report of the magistrates, to bear the aspect of a deed

[26]

of charity; and the poor outcast according to them, was sent to the gaol for shelter, and to be taken care of! What kind of shelter was given to him, and what degree of care was exercised towards this poor human brother of the rector, may be inferred from the fact that he was found dead, after the lapse of a few days> in such a horrible place as the unventilated privy of a prison, where, during the whole time of his unlawful imprisonment, he had sat, and eaten, and drunk, and slept, until he slept the sleep of death. Surely, if this imitator of the Good Samaritan had wished to exercise the charity towards a suffering fellow-creature for which he would claim credit in this case, the spacious premises of the Morant Bay rectory, with its many out-rooms, might have furnished a less repulsive place of shelter; and the rector's ample income, derived from the public purse, might have furnished a little plain food to relieve his necessities, instead of turning him over to the cruel fate which befell him. A wondrous exercise of Christian charity, truly, to send a sick person,to a gaol, to be fed, not at his own, but at the parochial expense!

The specious pretext was allowed to pass, and Mr. Gordon was censured for having called in question the humanity of the rector; and, further to throw dust in the eyes of the public, Mr. Gordon was also deprived by Governor Eyre of the commissions he held as a magistrate of several parishes. Strange to say, he failed to obtain redress of this grievance at the Colonial Office, although the Colonial Secretary, the Duke of Newcastle, censured both Mr. Eyre and the magistrates for their conduct in connexion with this inquiry in the following severe language: ' I am unable to concur with you, ' says his grace, in a despatch addressed to Governor Eyre, " in the views which you have taken of the

[27]

proceedings of the justices; nor can I regard the recapitulation .contained in your despatch No. 52 as an accurate and complete statement of the facts disclosed in the evidence On the evidence of the gaoler there can be no

doubt that the gross and disgraceful abuses charged by Mr. Gordon against the lock-up ' house did exist in it up to the time when it was visited by Mr. Gordon

When the justices, finding the lock-up house in this state, then simply resolved that it was a very good one, without the slightest notice of the scandalous abuses which had been proved against it, they evaded the whole question; and when they refused to hear eleven out of fourteen witnesses tendered by Mr. Gordon, on the ground that the evidence proffered related not ta the then, but to the past, state of the ' lock-up house, they betrayed their duty.''

There can be no doubt that this oppression of Mr. Gordon, because of his attempt to redress the grievances which the case of this poor man disclosed, gave intensity to the feeling of dissatisfaction already widely prevailing in the parish, and tended further to destroy all confidence in the integrity both of the parochial authorities and of the island government. And there can be as little doubt that this effort of Mr. Gordon to correct the abuses existing in the parish — rendered abortive ta a great extent by partiality and injustice — awakened towards him that bitter hostility on the part of the dominant faction in the parish and of Governor Eyre, that culminated in his murder. Neither the one nor tie other could readily forgive the man who had brought upon them such severe condemnation from the Colonial Office, and exposed them to so public a humiliation.

Mr. Gordon aggravated the unkindly feeling with which the Governor regarded him by the course he took as a member of the local parliament in opposing official

[28]

corruption and peculation. A notorious fraud had been perpetrated, well known as " the tramway swindle,' whereby the public revenue which the people were heavily taxed to sustain was defrauded of many thousand pounds. Gross negligence and unfaithfulness on the part of Mr. Eyre, as the head of the government, were alleged in connexion with this business, and he was subjected to heavy censure from many quarters, especially from the Hon. George Price, a leading member of the local government, who, in a large and well- written pamphlet, exposed, with scathing rebuke, the culpability of the Governor, and the indifference of the Colonial Office to the misconduct of its nominees in office. But from none did Mr. Eyre experience more caustic condemnation than from Mr. Gordon, who, in his place as a legislator, inveighed loudly against the corruption which laid the people open to be plundered of their hard earnings by greedy and dishonest officials. This was not all. A grant of £1000 had been voted by the Legislature for sundry repairs to be done to the official residence of the Governor. In violation of all propriety, a considerable part, some say £200, of this amount was used for the purchase of a piano, which would of course be more for the Governor's family use than the public service, arid, whenever he should remove from the government, would very likely be included and sold in the catalogue of his personal effects. This misappropriation of funds, voted for a different purpose, was exposed and commented upon in the Legislature by Mr. Gordon, and the amount had to be refunded. It is not difficult to conceive how a circumstance of this kind, more than anything else, would add intensity to the bitterness of those feelings with which the Governor regarded Mr. Gordon; and it sheds a gloomy light upon the proceedings of the Jamaica authorities in

[29]

connection with the arrest and condemnation of that unfortunate gentleman.

A further mortification was brought upon the Governor, through Mr. Gordon's instrumentality, in the successful opposition he gave to sundry favourite measures recommended by Mr. Eyre to the colonial legislature. Amongst these were the construction of a dock at Kingston, which he opposed on the ground that it was unconstitutional to, tax the whole of the people for what was really a private and speculative enterprise, and for the sole advantage of a small mercantile portion of the community. There were also bills passed on the Governor's recommendation to authorize capital punishment for petty offences, and to re-establish a district prison at Port Maria in a most unwholesome locality, and providing that hard labour should include the treadmill, shot drill, and crank These Mr. Gordon resisted, as involving a return to the abolished barbarities of past evil times. Unable to resist the influence in the local legislature which the Governor was able to exert there to carry these objectionable measures through, Mr. Gordon exposed and protested against their evil tendency in a well-written letter to the Colonial Secretary, and succeeded in obtaining their disallowance by the Crown; thereby, doubtless, exasperating in no small degree the dislike with which he was regarded by the Governor and the servile men who served his purposes in the two legislative bodies.*

The following are extracts from Mr. Gordon's letter to the Colonial Secretary:

"Sir, — I have to bring before your notice, on behalf of the people of this country, the following facts, which are submitted as grievances. From gross mismanagement and for wasteful purposes, the taxation of the country is increased The tramroad affair, besides having involved the country in a heavy expenditure, has also, by interfering with the principal public road, caused serious loss of stock to the passengers. The Governor, in his

[80]

Next came the celebrated Underhill letter to which Mr. Eyre attached so much importance as causing tube outbreak, forgetting that he himself was solely responsible for the agitation it produced in the island, inasmuch as it was he who gave it all the publicity it acquired. This letter, containing a temperate and able statement of the grievances under which the labouring classes of Jamaica were ground to the earth, was addressed to the Colonial Minister, Mr. Card well, who referred it in an official despatch to Mr. Eyre, for him to report upon it. With unpardonable indiscretion, if he really

opening speech, recommends a project of a dock, which certainly is not one for which the people should he taxed. Is it constitutional to tax the people for speculative enterprises? This is a measure which, if allowed to take effect, will create new heart-churnings in the minds of the inhabitants nearly, and is a great public wrong.

"A Bill was passed to inflict corporal punishment for petty offences

This measure is strictly one aimed against the lower classes, who just now are in a state of great destitution. If yon could only he hold them, your feelings

"A Bill was also passed to re-establish a district prison at Port Maria, which provides that hard labour shall include the hand-mill, shot-drill, and crank. Fort Maria is the grave of Jamaica. Yet the prison, which was abolished, is again to be re-established, with the iron shackles; to which the unfortunate prisoners have been consigned by the present Governor, with hard labour. From the depreciated state of health to which the prisoners must be reduced at Fort Maria, many of them will leave the prison to be for ever after worthless, and a tax upon society. When it is remembered that many are sent to prison for minor offences — in many cases wrongfully, and under wrong sentences — by erring judgments and unlearned justices, it does seem that it is a most cruel proceeding. I only write from the stem obligations of a sense of justice and common humanity."

[31]

believed in the wide-spread disaffection reported by him to exist amongst the people, Mr. Eyre took measures which caused Dr. Underhill's letter to be circulated in every newspaper printed in the colony, calling forth an almost universal response of such a character as indicated how general was the dissatisfaction among all classes of the community with the state of affairs and the government of the island. At the public meetings, held in the several parishes, Mr. Gordon took a prominent part in exposing existing abuses, and thus further incurred the enmity of the Governor, who appears to have been rendered furious by the opposition to his own grovelling, short-sighted policy which these meetings developed. This was evident from the significant fact, that when martial law was proclaimed, a large number, besides the unfortunate Gordon, who had taken part in these public meetings, were pounced upon by Governor Eyre and his agents and made prisoners, being sent to Morant Bay, and delivered over to the tender mercies of Nelson and Ramsay, under the impudent pretext that they were parties to the Morant Bay outbreak, and concerned in the imaginary plot which the Governor's own cowardice had conjured up; as if it were probable that planters, legal and medical practitioners, editors of newspapers, and members of the Legislature, all of them white men, or so nearly approaching it as to be married into respectable white families, and all of them in easy, if not affluent, circumstances, would enter into a conspiracy with the Negroes to assassinate all the white and coloured inhabitants, — including, of course, by inference, themselves and their own families — that the blacks might possess the island for themselves. A more palpable absurdity could scarcely have been conceived. It is remarkable that the whole of those men who were

[32]

arrested by command of Governor Eyre, and ignominiously hurried off to Morant Bay, to be tried like Gordon by court-martial, were parties who had taken a prominent share in the Tindethill meetings, so called

It was no relenting on the part of Mr. Eyre that saved these innocent men from sharing the fate of Gordon; but the misgivings which arose, rather tardily, in the minds of some of the principal military authorities as to the legality of trying and executing civilians by military tribunals, for alleged political offences committed by them long anterior to the existence of martial law; a procedure which the charge of the Lord Chief Justice of England stigmatizes with the guilt of murder, inasmuch as it is putting men to death without any authority of law.

CHAPTER III.

The preceding observations serve to explain what had been for a long time the condition of affairs, and what was the state of public feeling in the island, when, on Saturday, the 7th of October, two planter justices of the peace — Mr. Walton, the owner of a plantation in the vicinity, who was among the slain of the following week, and another — were sitting in the Morant Bay court-house, adjudicating cases which planters ought not to have been competent judicially to meddle with, inasmuch as they involved questions of land occupation, and other matters upon which planters were not likely to give a fair and unbiassed judgment; it being well understood that planter magistrates would help and favour each other, and hold on to planter interests in all questions at issue between the labourers and their employers. For some cause never explained, the decisions of the two Magistrates on this occasion failed to give satisfaction to the black people, who filled the court-house in considerable numbers; and they expressed their discontent, according to their wont, in audible murmurs. This gave offence to the magisterial dignitaries, who ordered that the murmurers should be taken into custody by the police. On hearing this order given, the people immediately retired from the court-house; and outside the officers attempted to arrest one of the number, whom they had marked as signifying dissatisfaction with the proceedings of the magistrates. This act was alike illegal and unwise, as the police had no authority without a warrant to arrest men out of the

[34]

court, and the evil complained of had ceased as soon as notice was taken of it. It was resisted by the man's friends; and the attempt proved abortive, having no other result than to increase the indignation of the people, already smarting under grievous wrongs. If the magistrates had exercised the forbearance which any English judge would have shown, and let the matter rest here, they would have acted discreetly; but on the following Monday, when the court resumed its sittings, a black man named Paul Bogle, (who from his superior intelligence exerted considerable influence amongst the labourers in the neighbourhood in which he lived,) when the Magistrates, in an alleged case of trespass, sentenced a person to fine or imprisonment, interposed his advice to the man, as he had a perfect right to do, to give notice that he would appeal against the Magistrates' decision. Irritated by Bogle's interference, the Magistrates, yielding to spiteful feeling, very foolishly fell back upon and revived the old case, and proceeded to issue warrants against Bogle and several others on the charge of interfering with the police in the execution of their duty. This amounted to something like a declaration of war against the black people concerned, who had certainly done nothing more than resist, very unwisely perhaps, the illegal apprehension of a man without a warrant; and it could scarcely have any other effect, considering the provocation already given, than to stir them up to resist violence with violence.

The next day a posse of officers, ludicrously small, (as it consisted of only three or four men,) was sent to apprehend the offenders, amounting to some twenty-eight, whose names were included in the warrants Wrought up by this time to something approaching desperation. Bogle and his associates resisted the officers

[35]

and made them prisoners; dismissing them, however, after a short time, without harm or insult. Thus the magistrates went blundering on, and by their reckless intemperate proceedings raised a spirit which they could neither subdue nor control.

On Wednesday, the 11th of October, the quarterly meeting of the parish Vestry was to be held; and the parish authorities, with the Custos at their head, alarmed at the demonstrations of the last few days, and without sufficient discretion to remonstrate with the excited and misguided people, and endeavour to bring them to reason by mild and conciliatory measures, could think of nothing but a resort to brute force. Accordingly a despatch was sent off to the Governor, giving an exaggerated account of what had occurred, and calling for military aid. Meanwhile, a small body of volunteers belonging to the parish was summoned to Morant Bay, to afford protection to the Vestry, because it was rumoured that Paul Bogle, and a large number of the people with him, intended that day to go down to the Bay. A more unfortunate step could not have been taken; and to this foolish act of calling out the volunteers may be attributed all the deplorable results which ensued. Even as it was, if there had been amongst the authorities one person gifted with cool self-possession and sound discretion, to go out and advise the people to abstain from violence, there would have been no outbreak, and the fatal collision of that day would have been prevented. It was an unfortunate circumstance that Mr. Gordon was, through indisposition, prevented from attending that vestry meeting, of which he was a member; for, no doubt, had he been present, he would have pointed out to the people that they were acting unadvisedly, and taking an unwise course to obtain redress of their grievances: and a few words

[36]

from him, whom they knew and respected, would have been sufficient. But he was not there, through illness; and there was not one present, either clergyman, magistrate, or vestryman, that had the courage and good sense to do what the emergency and humanity demanded.

The meeting of the Vestry took place, and the business proceeded to its close without any interruption. The members of the Vestry were about to regale themselves with the dinner usually provided on such occasions, at the expense of the parish; but before the viands, which were in course of preparation, could be served, a large assembly of people made their appearance at the entrance of the square in which the court-house stood. It has never been explained what specific purpose they had in view, in marching into the town as they did; but it was probably nothing more than was meant by the late Reform gatherings in London, which were designed for no purposes of violence, but as demonstrations, on the part of those who took part in them, to assert what they conceived to be their claims to right and justice. The elaborate investigations of the Royal Commission, directed especially to this point, failed to elicit the slightest evidence that any plot existed amongst the Negroes. They brought no fire-arms with them; for those which they afterwards used they took from the police station, after they found the volunteers drawn up in hostile array to receive them; and the fact that those who were killed after the attack upon the court-house were in most, if not all cases, beaten to death, and not hewn down, would show that they had not even armed themselves with the cutlass, a large knife, used as the chief implement of their daily toil. The conclusion to which we are brought by a fair consideration of all that has come to light is that the

[37]

assembling of the mob, upon the 11th of October, was an unpremeditated and ill-judged act, consequent upon the injudicious and culpable proceedings of the local authorities. The brutal and indiscriminate massacre of all who were connected with, or present at, the riot, who could have shed light upon the subject, has rendered it impossible that any satisfactory information can be obtained as to the views and purposes of the rioters; but the facts, that no traces of any plot or organization could be discovered; that they proceeded to Morant Bay, unarmed; that they did not injure, or attempt to injure, any individual, until they were fired upon, and a considerable number of them killed or wounded, — render it absurd to look upon the movement as an attempt at rebellion, or anything more than a sudden riot, capable of being altogether prevented by the exercise of something like discretion on the part of the unfortunate men in the court-house, who paid with their lives the penalty of those errors into which their fears hurried them.

This is fully borne out by the petition which was addressed to the Governor only the day before the riot took place, signed by James Dacres, Paul Bogle, James McLaren, and others, who were afterwards hurried to the gallows by military tribunals. In this remarkable document they complain of the conduct of the Magistrates; represent themselves as loyal to the Queen; express their belief that the attack made upon them by the police at Morant Bay (on the preceding Saturday) was an outrageous assault, and that they had the right to resist the arrest of innocent persons. They further complain of wrongs spreading over the past twenty-seven years, and call upon the Governor to protect them from the oppressions they were subject to; and intimate that if he will not do so they will be compelled

[38]to put their own shoulders to the wheel, with due obeisance to the laws of the Queen and country. The following is the petition of these oppressed villagers:

"We, the petitioners of St. Thomas-in-the-East, do send to inform Your Excellency of the mean advantages that has been taken of us from time to time; and more especially this present time, when, on Saturday, the 7th of this month, an outrageous assault was committed on us by the policemen of this parish, by order of the justices, which occasioned an outbreaking; for which warrants have been issued against innocent persons, which we were compelled to resist. We therefore call upon Your Excellency for protection, seeing we are Her Majesty 's loyal subjects; which protection, if refused we will be compelled to put our shoulders to the wheels, as we have been imposed upon for a period of twenty-seven years, with due obeisance to the laws of our Queen and country, and we can no longer endure the same.

"Therefore is our object of calling upon Your Excellency; and your petitioners, as in duty bound, will ever pray. "James Dacres, Paul Bogle, James M'Laren, and others."

This certainly is not the language of those who were engaged in and about to carry into effect, a deadly conspiracy against the Government, and to destroy the white and coloured people; but that of men honestly appealing to the right quarter for the redress of crying grievances; and is, in itself, sufficient proof that the riot which took place on the following day must have been unpremeditated, provoked by circumstances which occurred immediately after the petition had been forwarded to the Governor.

The conduct of Mr. Eyre with regard to this important paper was most extraordinary and reprehensible; and serves to show his utter want of candour, and the little reliance that is to be placed upon his representations of the outbreak, and the causes which produced it.— Thia

[39]

petition was sent by a special messenger; and it is in evidence that it was placed in the Governor's hands on the forenoon of the 11th, a very short time after he had received the communication of the Custos, requesting military aid. Had he been a wise and prudent man, and equal to the duties of his position, he would have acted as his predecessor in office, Earl Mulgrave, did on a somewhat similar occasion. Repairing without delay to the spot where mischief was evidently threatening, and acquainting himself with the real merits of the case, he would have addressed himself to the application of the remedy required. But, strange to say, with an indifference which shows in a striking point of view his unfitness for the position he occupied, he simply gave orders for a military force to be sent, suppressed the petition of the complaining Negroes, and betook himself to a dinner-party in the mountains. And, after the collision had taken place which these two communications showed to be imminent, he altogether put away the important petition of the oppressed people which had been conveyed to him, making no mention of it in his official dispatches to the Colonial Office. It would probably never have been brought forward, important as it is in throwing light upon the events of those few memorable days and the real purposes of the unfortunate Negroes, had he not been compelled to produce it through questions put to him by the counsel employed by the Jamaica Committee to watch the proceedings of the Royal Commission.

But yet more strange is the fact that the poor fellow who carried the petition to the Governor was punished with a severe flogging by the notorious Ramsay, whether with the connivance and sanction of Mr. Eyre does not very clearly appear; but it is difficult to imagine how, without such connivance, Ramsay could have be

[40]

come aware of the circumstances. And, as far as can be ascertained, every person who signed that petition, or was privy to it in any way, was mercilessly hunted down and put to death.

The unhappy events which occurred on the 11th of October are matters of sufficient notoriety. That the conduct of the complaining Negroes, in marching as they did to Morant Bay on the day of the vestry-meeting, was unwise and culpable, is not to be denied; but, even then, no such sad results as followed would have ensued, but for the much more culpable proceedings of the Custos, and those who were assembled with him in the court-house. Terrified beyond all reason and propriety, it seems never to have occurred to them that, before resorting to extremities, some one ought to go out and remonstrate with the advancing crowd, and advise them to return quietly to their homes, and to keep the peace. Or, if it did occur to them, no one had sufficient courage to take this reasonable course; but, swift to shed blood, the Riot Act is hastily read, (so it is affirmed,) — not one, perhaps, of all the crowd being aware of the proceeding, or understanding what it meant, — and the volunteers, a feeble company of some eighteen or twenty men, are ordered at once to fire upon the people. More sensible and less sanguinary men would have tried the effect of blank cartridges before proceeding to the fatal extremity of the rifle ball; but no such prudent and temperate proceeding was thought of, and the volunteers, under the direction of the magistrates, sent a deadly volley into the midst of the advancing crowd. This was repeated; and between thirty and forty, killed or grievously wounded, fell to the ground. It wanted only this to bring on a fearful crisis, which might have been avoided.

The black people of our colonies are by no means

[41]