"[U]pper class males have their own attitudes of privilege and poise and some of these paintings reveal the psychology of the unconscious advantages of their class. James Tissot's The Circle of Rue Royale (1868) displays a group of men with prerogatives displaying themselves to each other on the neo-classical pavilion of the Gabriel balcony of the Jockey Club. Located in the Hôtel Scribe at this time, the Jockey Club was dedicated, as it said, to "the improvement of horse breeding in France".

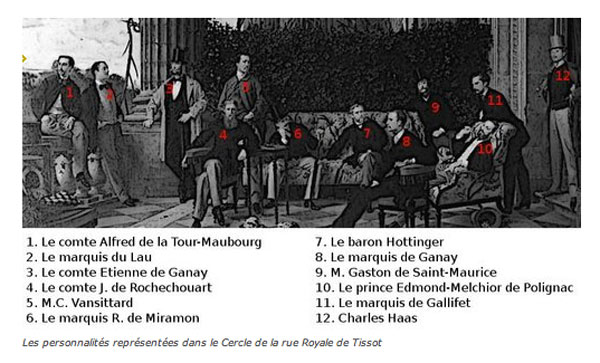

According to the Musée d'Orsay, the scene is set on "one of the balconies of the Hôtel de Coislin" and it should be noted that each languid aristocrat is a portrait of actual pedigreed males: the Comte Alfred de la Tour-Maubourg (1834-1891) the Marquis Alfred du Lau d'Allemans (1833-1919), the Comte Étienne de Ganay (1833-1903), the Capitaine Coleraine Vansittart (1833-1886), the Marquis René de Miramon (1835-1882), the Comte Julien de Rochechouart (1828-1897), the Baron Rodolphe Hottinguer (1835-1920), the Marquis Charles-Alexandre de Ganay (1803-1881), the Baron Gaston de Saint-Maurice (1831-1905), the Prince Edmond de Polignac (1834-1901), the Marquis Gaston de Galliffet (1830-1909), and Charles Haas (1833-1902).

Tissot's aristocrats at The Jockey Club

No one depicted this kind of rarified male better than Tissot, a French artist in exile, who lived and worked in London, the original home of the original Jockey Club and perfectly captured the aristocratic male at his apogee in the twilight of the nineteenth century. To my mind, the greatest portraits of the these decades are devoted, not to women, but to these peacock males: John Singer Sargent's Dr. Pozzi at Home (1881) and most of all, Tissot's portrait of Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (1870).

(Click on image to enlarge)

Alone amidst incongruous floral furniture, the British Captain of the Royal Horse Guards lounges at his ease, mustaches waxed and uptilted, cigarette at attention between his graceful fingers. To the eyes of an untutored American, Burnaby looks "French, " but "Fred", as he was called, was decidedly English. In fact his mannered style, the epitome of male mannerism, was the very essence of all that was the British aristocracy at its peak and it was this aspect of all things English that wafted across the Chanel as "Anglomania."

The French aristocrats at the Jockey Club are echoes and copies of Burnaby, most of them without his adventurousness and bravery, as are their favorite sports from yachting to tennis to horseracing to the very concept of "sport" itself - all British exports...

These wealthy men seem idle and without purpose; they are rarely engaged in any meaningful activity and, in their pointless lives, seem to exemplify the alienation discussed by the catalogue."

[Source: jeannewillette.com/2012/12/15/impressionism-fashion-and-modernity-at-the-met-part-one (dated 15.12.2013, accessed 13.3.2013). By 2015 this article has migrated to arthistoryunstuffed.com/impressionism-fashion-and-modernity-part-two. See also parts one, three, and four.]